Noise handshakes as key-exchange mechanism for Waku

We provide an overview of the Noise Protocol Framework as a tool to design efficient and secure key-exchange mechanisms in Waku2.

Introduction

In this post we will provide an overview of how Waku v2 users can adopt Noise handshakes to agree on cryptographic keys used to securely encrypt messages.

This process belongs to the class of key-exchange mechanisms, consisting of all those protocols that, with different levels of complexity and security guarantees, allow two parties to publicly agree on a secret without letting anyone else know what this secret is.

But why do we need key-exchange mechanisms in the first place?

With the advent of public-key cryptography, it become possible to decouple encryption from decryption through use of two distinct cryptographic keys: one public, used to encrypt information and that can be made available to anyone, and one private (kept secret), which enables decryption of messages encrypted with its corresponding public key. The same does not happen in the case of symmetric encryption schemes where, instead, the same key is used for both encryption and decryption operations and hence cannot be publicly revealed as for public keys.

In order to address specific application needs, many different public, symmetric and hybrid cryptographic schemes were designed: Waku v1 and Waku v2, which inherits part of their design from the Ethereum messaging protocol Whisper, provide support to both public-key primitives (ECIES, ECDSA) and symmetric primitives (AES-256-GCM, KECCAK-256), used to sign, hash, encrypt and decrypt exchanged messages.

In principle, when communications employ public-key based encryption schemes (ECIES, in the case of Waku), there is no need for a key-agreement among parties: messages can be directly encrypted using the recipient's public-key before being sent over the network. However, public-key encryption and decryption primitives are usually very inefficient in processing large amount of data, and this may constitute a bottleneck for many of today's applications. Symmetric encryption schemes such as AES-256-GCM, on the other hand, are much more efficient, but the encryption/decryption key needs to be shared among users beforehand any encrypted messages is exchanged.

To counter the downsides given by each of these two approaches while taking advantage of their strengths, hybrid constructions were designed. In these, public-key primitives are employed to securely agree on a secret key which, in turn, is used with a symmetric cipher for encrypting messages. In other words, such constructions specify a (public-key based) key-agreement mechanism!

Waku, up to payload version 1, does not implement nor recommend any protocol for exchanging symmetric ciphers' keys, leaving such task to the application layer. It is important to note that the kind of key-agreement employed has a direct impact on the security properties that can be granted on later encrypted messages, while security requirements usually depend on the specific application for which encryption is needed in the first place.

In this regard, Status, which builds on top of Waku, implements a custom version of the X3DH key-agreement protocol, in order to allow users to instantiate end-to-end encrypted communication channels. However, although such a solution is optimal when applied to (distributed) E2E encrypted chats, it is not flexible enough to fit or simplify the variety of applications Waku aims to address. Hence, proposing and implementing one or few key-agreements which provide certain (presumably strong) security guarantees, would inevitably degrade performances of all those applications for which, given their security requirements, more tailored and efficient key-exchange mechanisms can be employed.

Guided by different examples, in the following sections we will overview Noise, a protocol framework we are currently integrating in Waku, for building secure key-agreements between two parties. One of the great advantage of using Noise is that it is possible to add support to new key-exchanges by just specifying users' actions from a predefined list, requiring none to minimal modifications to existing implementations. Furthermore, Noise provides a framework to systematically analyze protocols' security properties and the corresponding attacker threat models. This allows not only to easily design new key-agreements eventually optimized for specific applications we want to address, but also to easily analyze or even formally verify any of such custom protocol!

We believe that with its enormous flexibility and features, Noise represents a perfect candidate for bringing key-exchange mechanisms in Waku.

The Diffie-Hellman Key-exchange

The formalization of modern public-key cryptography started with the pioneering work of Whitefield Diffie and Martin Hellman, who detailed one of the earliest known key-agreement protocols: the famous Diffie-Hellman Key-Exchange.

Diffie-Hellman (DH) key-exchange is largely used today and represents the main cryptographic building block on which Noise handshakes' security is based.

In turn, the security of DH is based on a mathematical problem called discrete logarithm which is believed to be hard when the agreement is practically instantiated using certain elliptic curves defined over finite fields .

Informally, a DH exchange between Alice and Bob proceeds as follows:

- Alice picks a secret scalar and computes, using the underlying curve's arithmetic, the point for a certain pre-agreed public generator of the elliptic curve . She then sends to Bob.

- Similarly, Bob picks a secret scalar , computes and sends to Alice.

- By commutativity of scalar multiplication, both Alice and Bob can now compute the point , using the elliptic curve point received from the other party and their secret scalar.

The assumed hardness of computing discrete logarithms in the elliptic curve, ensures that it is not possible to compute or from and , respectively. Another security assumption (named Computational Diffie-Hellman assumption) ensures that it is not possible to compute from , and . Hence the point shared by Alice and Bob at the end of the above protocol cannot be efficiently computed by an attacker intercepting and , and can then be used to generate a secret to be later employed, for example, as a symmetric encryption key.

On a side note, this protocol shows the interplay between two components typical to public-key based schemes: the scalars and can be seen as private keys associated to the public keys and , respectively, which allow Alice and Bob only to compute the shared secret point .

Ephemeral and Static Public Keys

Although we assumed that it is practically impossible for an attacker to compute the randomly picked secret scalar from the corresponding public elliptic curve point, it may happen that such scalar gets compromised or can be guessed due to a faulty employed random number generator. In such cases, an attacker will be able to recover the final shared secret and all encryption keys eventually derived from that, with clear catastrophic consequences for the privacy of exchanged messages.

To mitigate such issues, multiple DH operations can be combined using two different types of exchanged elliptic curve points or, better, public keys: ephemeral keys, that is random keys used only once in a DH operation, and long-term static keys, used mainly for authentication purposes since employed multiple times.

Just to provide an example, let us suppose Alice and Bob perform the following custom DH-based key-exchange protocol:

- Alice generates an ephemeral key by picking a random scalar and sends to Bob;

- Similarly, Bob generates an ephemeral key and sends to Alice;

- Alice and Bob computes and from it derive a secret encryption key .

- Bob sends to Alice his static key encrypted with .

- Alice encrypts with her static key and sends it to Bob.

- Alice and Bob decrypt the received static keys, compute the secret and use it together with to derive a new encryption key to be later used with a symmetric cipher.

In this protocol, if Alice's and/or Bob's static keys get compromised, it would not possible to derive the final secret key , since at least one ephemeral key among and has to be compromised too in order to recover the secret . Furthermore, since Alice's and Bob's long-term static keys are encrypted, an attacker intercepting exchanged (encrypted) public keys will not be able to link such communication to Alice or Bob, unless one of the ephemeral key is compromised (and, even in such case, none of the messages encrypted under the key can be decrypted).

The Noise Protocol Framework

In previous section we gave a small intuition on how multiple DH operations over ephemeral and static users' public keys can be combined to create different key-exchange protocols.

The Noise Protocol Framework, defines various rules for building custom key-exchange protocols while allowing easy analysis of the security properties and threat models provided given the type and order of the DH operations employed.

In Noise terminology, a key-agreement or Noise protocol consists of one or more Noise handshakes. During a Noise handshake, Alice and Bob exchange multiple (handshake) messages containing their ephemeral keys and/or static keys. These public keys are then used to perform a handshake-dependent sequence of Diffie-Hellman operations, whose results are all hashed into a shared secret key. Similarly as we have seen above, after a handshake is complete, each party will use the derived secret key to send and receive authenticated encrypted data by employing a symmetric cipher.

Depending on the handshake pattern adopted, different security guarantees can be provided on messages encrypted using a handshake-derived key.

The Noise handshakes we support in Waku all provide the following security properties:

- Confidentiality: the adversary should not be able to learn what data is being sent between Alice and Bob.

- Strong forward secrecy: an active adversary cannot decrypt messages nor infer any information on the employed encryption key, even in the case he has access to Alice's and Bob's long-term private keys (during or after their communication).

- Authenticity: the adversary should not be able to cause either Alice or Bob to accept messages coming from a party different than their original senders.

- Integrity: the adversary should not be able to cause Alice or Bob to accept data that has been tampered with.

- Identity-hiding: once a secure communication channel is established, a passive adversary should not be able to link exchanged encrypted messages to their corresponding sender and recipient by knowing their long-term static keys.

We refer to Noise specification for more formal security definitions and precise threat models relative to Waku supported Noise Handshake patterns.

Message patterns

Noise handshakes involving DH operations over ephemeral and static keys can be succinctly sketched using the following set of handshake message tokens: e,s,ee,se,es,ss.

Tokens employing single letters denote (the type of) users' public keys: e refers to randomly generated ephemeral key(s), while s indicates the users' long-term static key(s).

Two letters tokens, instead, denotes DH operations over the two users' public keys the token refers to, given that the left token letter refers to the handshake initiator's public key, while the right token letter indicates the used responder's public key. Thus, if Alice started a handshake with Bob, the es token will shortly represent a DH operation among Alice's ephemeral key e and Bob's static key s.

Since, in order to perform any DH operations users need to share (or pre-share) the corresponding public keys, Noise compactly represents messages' exchanges using the two direction -> and <-, where the -> denotes a message (arbitrary and/or DH public key) from the initiator to the responder, while <- the opposite.

Hence a message pattern consisting of a direction and one or multiple tokens such as <- e, s, es has to be interpreted one token at a time: in this example, the responder is sending his ephemeral and static key to the initiator and is then executing a DH operation over the initiator's ephemeral key e (shared in a previously exchanged message pattern) and his static key s. On the other hand, such message indicates also that the initiator received the responder's ephemeral and static keys e and s, respectively, and performed a DH operation over his ephemeral key and the responder's just received static key s. In this way, both parties will be able to derive at the end of each message pattern processed the same shared secret, which is eventually used to update any derived symmetric encryption keys computed so far.

In some cases, DH public keys employed in a handshake are pre-shared before the handshake itself starts. In order to chronologically separate exchanged keys and DH operations performed before and during a handshake, Noise employs the ... delimiter.

For example, the following message patterns

<- e

...

-> e, ee

indicates that the initiator knew the responder's ephemeral key before he sends his own ephemeral key and executes a DH operation between both parties ephemeral keys (similarly, the responder receives the initiator's ephemeral key and does a ee DH operation).

At this point it should be clear how such notation is able to compactly represent a large variety of DH based key-agreements. Nevertheless, we can easily define additional tokens and processing rules in order to address specific applications and security requirements, such as the psk token used to process arbitrary pre-shared key material.

As an example of Noise flexibility, the custom protocol we detailed above can be shortly represented as (Alice is on the left):

-> e

<- e, ee, s

-> s, ss

where after each DH operation an encryption key is derived (along with the secrets computed by all previously executed DH operations) in order to encrypt/decrypt any subsequent sent/received message.

Another example is given by the possibility to replicate within Noise the well established Signal's X3DH key-agreement protocols, thus making the latter a general framework to design and study security of many practical and widespread DH-based key-exchange protocols.

The Noise State Objects

We mentioned multiple times that parties derive an encryption key each time they perform a DH operation, but how does this work in more details?

Noise defines three state object: a Handshake State, a Symmetric State and a Cipher State, each encapsulated into each other and instantiated during the execution of a handshake.

The Handshake State object stores the user's and other party's received ephemeral and static keys (if any) and embeds a Symmetric State object.

The Symmetric State, instead, stores a handshake hash value h, iteratively updated with any message read/received and DH secret computed, and a chaining key ck, updated using a key derivation function every time a DH secret is computed. This object further embeds a Cipher State.

Lastly, the Cipher State stores a symmetric encryption k key and a counter n used to encrypt and decrypt messages exchanged during the handshake (not only static keys, but also arbitrary payloads). These key and counter are refreshed every time the chaining key is updated.

While processing each handshake's message pattern token, all these objects are updated according to some specific processing rules which employ a combination of public-key primitives, hash and key-derivation functions and symmetric ciphers. It is important to note, however, that at the end of each processed message pattern, the two users will share the same Symmetric and Cipher State embedded in their respective Handshake States.

Once a handshake is complete, users derive two new Cipher States and can then discard the Handshake State object (and, thus, the embedded Symmetric State and Cipher State objects) employed during the handshake.

These two Cipher states are used to encrypt and decrypt all outbound and inbound after-handshake messages, respectively, and only to these will be granted the confidentiality, authenticity, integrity and identity-hiding properties we detailed above.

For more details on processing rules, we refer to Noise specifications.

Supported Noise Handshakes in Waku

The Noise handshakes we provided support to in Waku address four typical scenarios occurring when an encrypted communication channel between Alice and Bob is going to be created:

- Alice and Bob know each others' static key.

- Alice knows Bob's static key;

- Alice and Bob share no key material and they don't know each others' static key.

- Alice and Bob share some key material, but they don't know each others' static key.

The possibility to have handshakes based on the reciprocal knowledge parties have of each other, allows designing Noise handshakes that can quickly reach the desired level of security on exchanged encrypted messages while keeping the number of interactions between Alice and Bob minimum.

Nonetheless, due to the pure token-based nature of handshake processing rules, implementations can easily add support to any custom handshake pattern with minor modifications, in case more specific application use-cases need to be addressed.

On a side note, we already mentioned that identity-hiding properties can be guaranteed against a passive attacker that only reads the communication occurring between Alice and Bob. However, an active attacker who compromised one party's static key and actively interferes with the parties' exchanged messages, may lower the identity-hiding security guarantees provided by some handshake patterns. In our security model we exclude such adversary, but, for completeness, in the following we report a summary of possible de-anonymization attacks that can be performed by such an active attacker.

For more details on supported handshakes and on how these are implemented in Waku, we refer to WAKU2-NOISE RFC.

The K1K1 Handshake

If Alice and Bob know each others' static key (e.g., these are public or were already exchanged in a previous handshake) , they MAY execute a K1K1 handshake. In Noise notation (Alice is on the left) this can be sketched as:

K1K1:

-> s

<- s

...

-> e

<- e, ee, es

-> se

We note that here only ephemeral keys are exchanged. This handshake is useful in case Alice needs to instantiate a new separate encrypted communication channel with Bob, e.g. opening multiple parallel connections, file transfers, etc.

Security considerations on identity-hiding (active attacker): no static key is transmitted, but an active attacker impersonating Alice can check candidates for Bob's static key.

The XK1 Handshake

Here, Alice knows how to initiate a communication with Bob and she knows his public static key: such discovery can be achieved, for example, through a publicly accessible register of users' static keys, smart contracts, or through a previous public/private advertisement of Bob's static key.

A Noise handshake pattern that suits this scenario is XK1:

XK1:

<- s

...

-> e

<- e, ee, es

-> s, se

Within this handshake, Alice and Bob reciprocally authenticate their static keys s using ephemeral keys e. We note that while Bob's static key is assumed to be known to Alice (and hence is not transmitted), Alice's static key is sent to Bob encrypted with a key derived from both parties ephemeral keys and Bob's static key.

Security considerations on identity-hiding (active attacker): Alice's static key is encrypted with forward secrecy to an authenticated party. An active attacker initiating the handshake can check candidates for Bob's static key against recorded/accepted exchanged handshake messages.

The XX and XXpsk0 Handshakes

If Alice is not aware of any static key belonging to Bob (and neither Bob knows anything about Alice), she can execute an XX handshake, where each party tranXmits to the other its own static key.

The handshake goes as follows:

XX:

-> e

<- e, ee, s, es

-> s, se

We note that the main difference with XK1 is that in second step Bob sends to Alice his own static key encrypted with a key obtained from an ephemeral-ephemeral Diffie-Hellman exchange.

This handshake can be slightly changed in case both Alice and Bob pre-shares some secret psk which can be used to strengthen their mutual authentication during the handshake execution. One of the resulting protocol, called XXpsk0, goes as follow:

XXpsk0:

-> psk, e

<- e, ee, s, es

-> s, se

The main difference with XX is that Alice's and Bob's static keys, when transmitted, would be encrypted with a key derived from psk as well.

Security considerations on identity-hiding (active attacker): Alice's static key is encrypted with forward secrecy to an authenticated party for both XX and XXpsk0 handshakes. In XX, Bob's static key is encrypted with forward secrecy but is transmitted to a non-authenticated user which can then be an active attacker. In XXpsk0, instead, Bob's secret key is protected by forward secrecy to a partially authenticated party (through the pre-shared secret psk but not through any static key), provided that psk was not previously compromised (in such case identity-hiding properties provided by the XX handshake applies).

Session Management and Multi-Device Support

When two users complete a Noise handshake, an encryption/decryption session - or Noise session - consisting of two Cipher States is instantiated.

By identifying Noise session with a session-id derived from the handshake's cryptographic material, we can take advantage of the PubSub/GossipSub protocols used by Waku for relaying messages in order to manage instantiated Noise sessions.

The core idea is to exchange after-handshake messages (encrypted with a Cipher State specific to the Noise session), over a content topic derived from the (secret) session-id the corresponding session refers to.

This allows to decouple the handshaking phase from the actual encrypted communication, thus improving users' identity-hiding capabilities.

Furthermore, by publicly revealing a value derived from session-id on the corresponding session content topic, a Noise session can be marked as stale, enabling peers to save resources by discarding any eventually stored message sent to such content topic.

One relevant aspect in today's applications is the possibility for users to employ different devices in their communications. In some cases, this is non-trivial to achieve since, for example, encrypted messages might be required to be synced on different devices which do not necessarily share the necessary key material for decryption and may be temporarily offline.

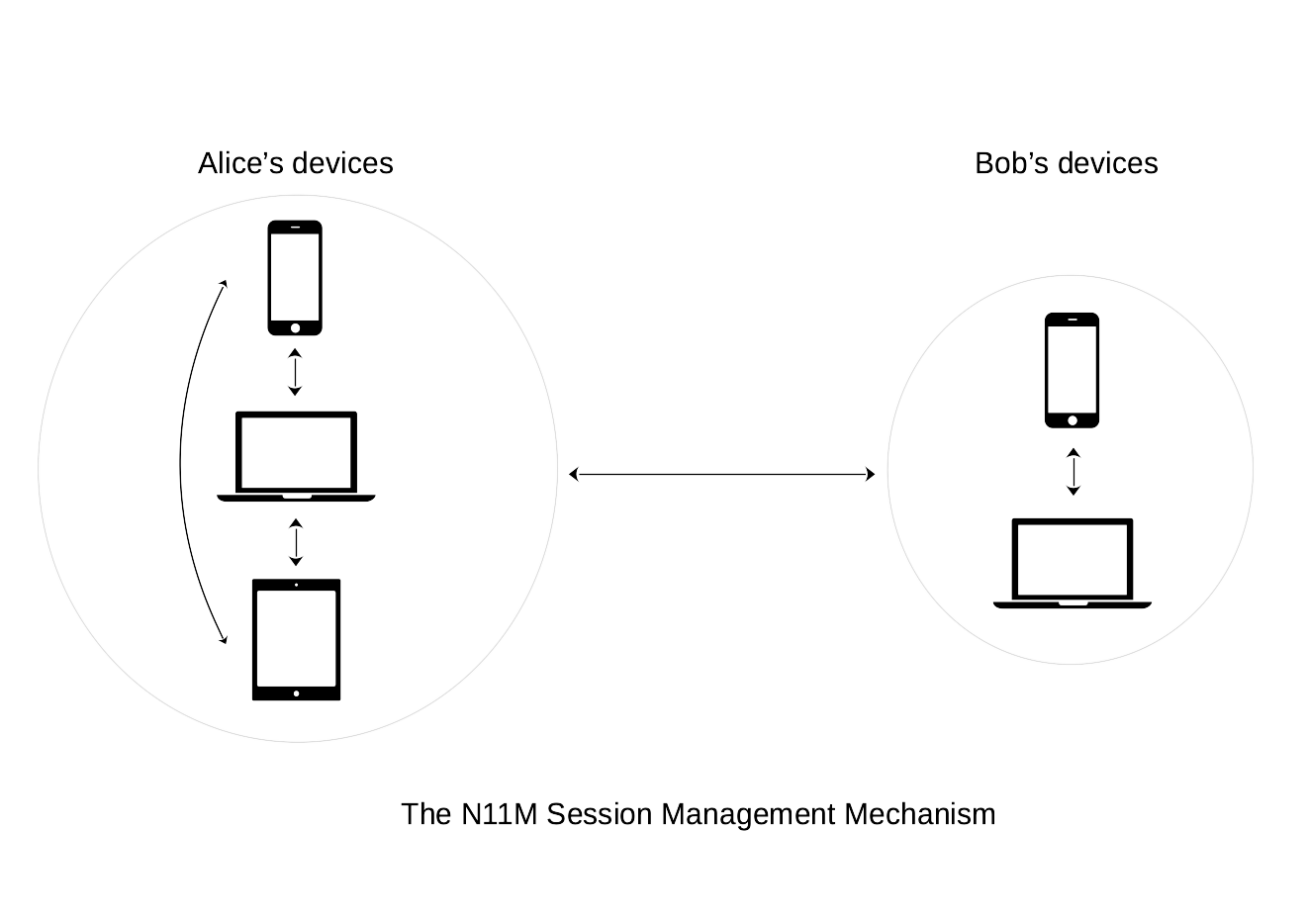

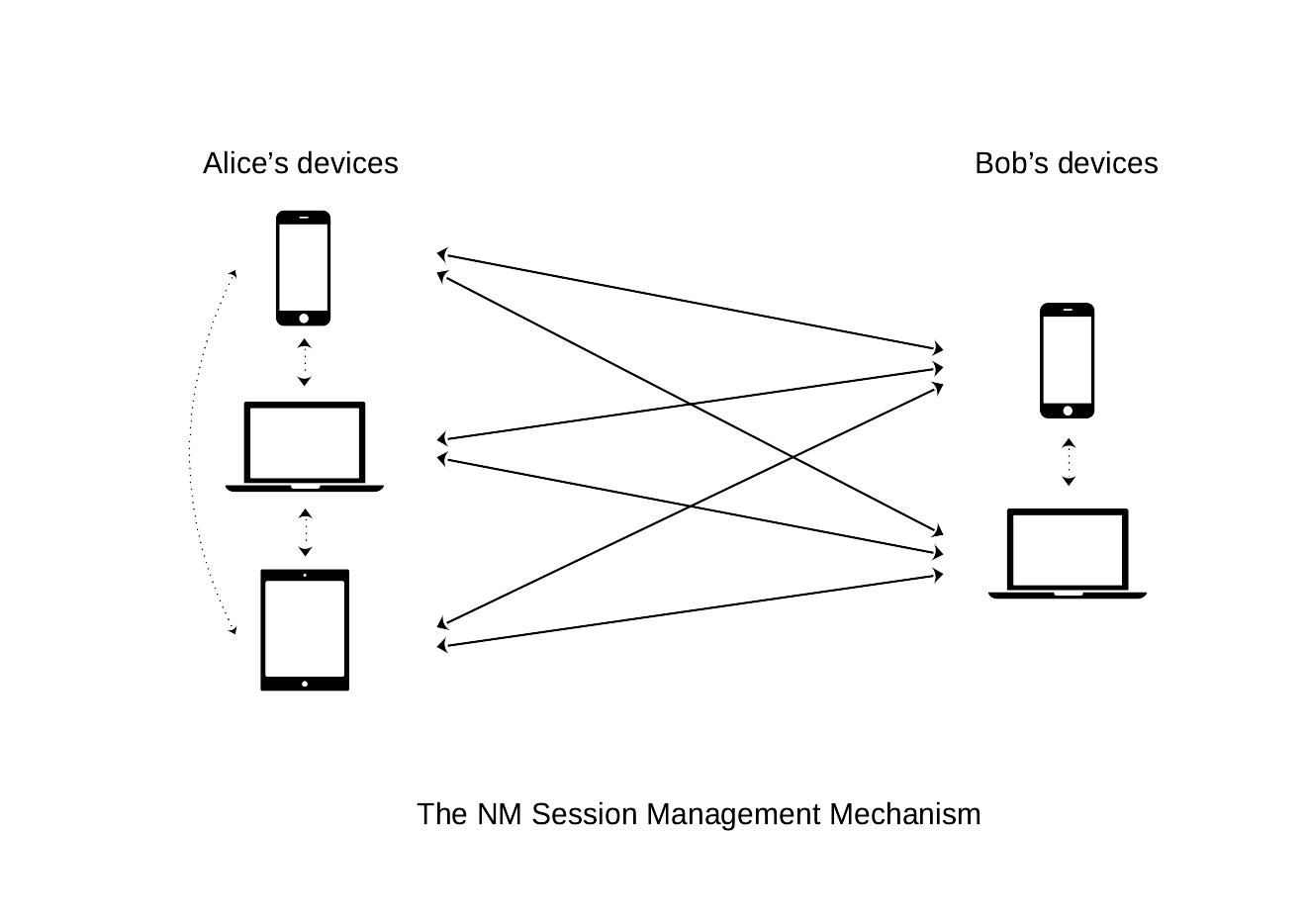

We address this by requiring each user's device to instantiate multiple Noise sessions either with all user's other devices which, in turn, all together share a Noise session with the other party, or by directly instantiating a Noise session with all other party's devices.

We named these two approaches and , respectively, which are in turn loosely based on the paper “Multi-Device for Signal” and Signal’s Sesame Algorithm.

Informally, in the session management scheme, once the first Noise session between any of Alice’s and Bob’s device is instantiated, its session information is securely propagated to all other devices using previously instantiated Noise sessions. Hence, all devices are able to send and receive new messages on the content topic associated to such session.

In the session management scheme, instead, all pairs of Alice's and Bob's devices have a distinct Noise session: a message is then sent from the currently-in-use sender’s device to all recipient’s devices, by properly encrypting and sending it to the content topics of each corresponding Noise session. If sent messages should be available on all sender’s devices as well, we require each pair of sender’s devices to instantiate a Noise session used for syncing purposes.

For more technical details on how Noise sessions are instantiated and managed within these two mechanisms and the different trade-offs provided by the latter, we refer to WAKU2-NOISE-SESSIONS.

Conclusions

In this post we provided an overview of Noise, a protocol framework for designing Diffie-Hellman based key-exchange mechanisms allowing systematic security and threat model analysis.

The flexibility provided by Noise components allows not only to fully replicate with same security guarantees well established key-exchange primitives such as X3DH, currently employed by Status TRANSPORT-SECURITY, but enables also optimizations based on the reciprocal knowledge parties have of each other while allowing easier protocols' security analysis and (formal) verification.

Furthermore, different handshakes can be combined and executed one after each other, a particularly useful feature to authenticate multiple static keys employed by different applications but also to ease keys revocation.

The possibility to manage Noise sessions over multiple devices and the fact that handshakes can be concretely instantiated using modern, fast and secure cryptographic primitives such as ChaChaPoly and BLAKE2b, make Noise one of the best candidates for efficiently and securely address the many different needs of applications built on top of Waku requiring key-agreement.

Future steps

The available implementation of Noise in nwaku, although mostly complete, is still in its testing phase. As future steps we would like to:

- have an extensively tested and robust Noise implementation;

- formalize, implement and test performances of the two proposed and session management mechanisms and their suitability for common use-case scenarios;

- provide Waku network nodes a native protocol to readily support key-exchanges, strongly-encrypted communication and multi-device session management mechanisms with none-to-little interaction besides applications' connection requests.

References

- 6/WAKU1

- 10/WAKU2

- 13/WAKU2-STORE

- 26/WAKU-PAYLOAD

- WAKU2-NOISE

- 37/WAKU2-NOISE-SESSIONS

- TRANSPORT-SECURITY

- The PubSub/GossipSub Protocols

- The Noise Protocol Framework

- The X3DH Key-agreement Protocol

- “Multi-Device for Signal”

- Signal’s Sesame Algorithm.

- Public-key cryptography

- Elliptic curves

- Elliptic Curve point multiplication

- Symmetric key algorithm

- Authenticated encryption

- Diffie-Hellman Key-Exchange

- The Discrete Logarithm Problem

- Computational Diffie-Hellman Assumption

- The ECIES Encryption Algorithm

- The ECDSA Signature Algorithm

- The Galois Counter Mode mode of operation

- The ChaChaPoly AEAD Cipher

- The BLAKE2b Hash Function

- The SHA-3 Hash Function